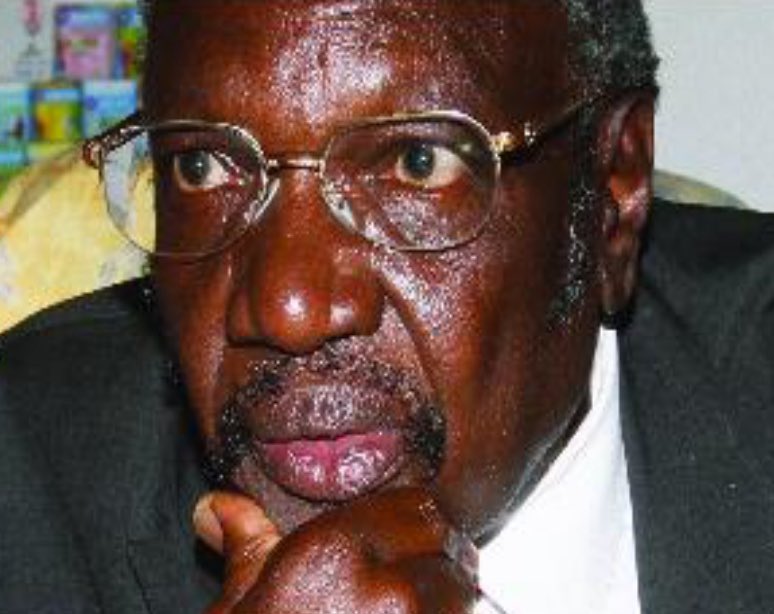

Early Life and Education

Arthur Obel grew up in rural Nyanza, Kenya, in modest circumstances. From an early age, he valued education and scientific inquiry. He earned a PhD in Therapeutics from the University of London in 1978. Later, he obtained an M.D. in Clinical Medicine from the University of Nairobi in 1987. Obel believed that modern medical science should address Africa’s urgent health challenges. This belief shaped his career and drove him to explore bold solutions for pressing problems.

Research Career and the Quest for Local HIV Solutions

In the late 1980s, Kenya faced a growing HIV/AIDS crisis. Antiretroviral therapy remained scarce and costly. Obel emerged as a leading, if controversial, researcher. He worked at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) as Chief Research Officer from 1989 to 1991.

Obel and his team developed Kemron, a drug they claimed could treat HIV/AIDS. They promoted it as an affordable, locally made solution. The drug gave hope to patients who had little access to conventional treatment. When clinical trials failed to confirm its effectiveness, Obel introduced a new formulation called Pearl Omega. He described it as a protease-inhibiting drug that could suppress the HIV virus. The initial rollout sparked national optimism. Citizens and government officials hoped for a home-grown cure to the epidemic.

Controversy and Scientific Rejection

Scientific authorities quickly challenged Obel’s claims. Independent studies and international reviews found no evidence that Kemron or Pearl Omega suppressed HIV. Experts criticized his methods and warned that the drugs offered false hope. The Kenya Medical Practitioners and Dentists Council deregistered him. Authorities banned Pearl Omega. Patients filed lawsuits claiming that Obel misled them. Despite these setbacks, Obel continued researching other treatments, though none gained scientific acceptance.

Broader Work and Contributions

Outside HIV research, Obel conducted legitimate studies on antibiotics, diabetes, gastrointestinal diseases, and other medical conditions. He published books on health, development, and social issues. Colleagues described him as a strict, determined, and uncompromising researcher. He believed in African-led solutions to African problems and often challenged conventional approaches in global medicine.

Death and Final Years

Arthur Obel died on 27 September 2025 after a prolonged illness, reportedly prostate cancer. Family, friends, colleagues, and mourners gathered at All Saints Cathedral, Nairobi, for a requiem mass. Speakers remembered him as a brilliant but polarizing figure. They emphasized his bold ideas, his willingness to challenge convention, and also the debates he sparked about scientific ethics.

Lessons

Obel remains a highly divisive figure in Kenya’s medical history. Supporters consider him a pioneer who sought local solutions when global medicine offered little hope. Critics call him reckless, accusing him of exploiting fear and desperation for personal gain.

His story highlights the tension between urgent public health needs and scientific rigor. The Kemron and Pearl Omega saga shows how quickly hope can turn into disappointment when claims lack evidence.

Obel’s career prompts reflection on the role of African scientists in global health. It raises questions about regulation, ethical responsibility, and the line between experimentation and exploitation.

Arthur Obel’s life and work remain part of Kenya’s history. He also stands as a complex, instructive figure whose legacy continues to spark discussion on science, ethics, and public health.

Also read: The Life, Service, and Tragic Death of Robert Ouko