Kenya’s public education system continues to lose millions due to poor planning and weak controls. A special audit has revealed that the government lost over Sh458 million across four financial years because of failures in the management of textbook funds in public schools.

The audit, conducted by the Office of the Auditor General, examined how capitation and infrastructure grants were used between the 2020/21 and 2023/24 financial years. What emerged was a pattern of inefficiency, weak oversight, and missed accountability at multiple levels.

Textbooks form the backbone of learning. When systems fail to deliver them correctly, learners pay the price. The audit shows that losses were not caused by a single mistake. Instead, they stemmed from systemic weaknesses that persisted over time. At the centre of the findings is the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development, which is responsible for coordinating textbook procurement. The audit faulted the institution for failing to include textbook purchases in its procurement plans, despite receiving billions of shillings for that purpose.

Billions Spent, But Books Still Missing

During the four year period under review, the State Department for Basic Education disbursed Sh27.9 billion to KICD to procure textbooks. The funds were meant to ensure timely delivery of learning materials to public schools across the country. However, the audit found that the department did not clearly explain how it transferred capitation funds to KICD. It also failed to disclose the criteria used in making the transfers. This lack of transparency weakened accountability from the start.

Contracts between KICD and publishers were clear. They outlined how many books each school should receive and where they should be delivered. Distribution schedules formed part of the contracts and guided delivery to individual schools.

Despite these clear terms, major gaps emerged. When auditors compared school records with KICD delivery receipts, they found missing textbooks worth nearly Sh296 million. These shortages affected hundreds of schools at all levels.

Some secondary schools missed up to 1,485 textbooks. Junior and primary schools also recorded significant shortfalls. These gaps meant that many learners lacked access to basic learning materials during critical stages of their education.

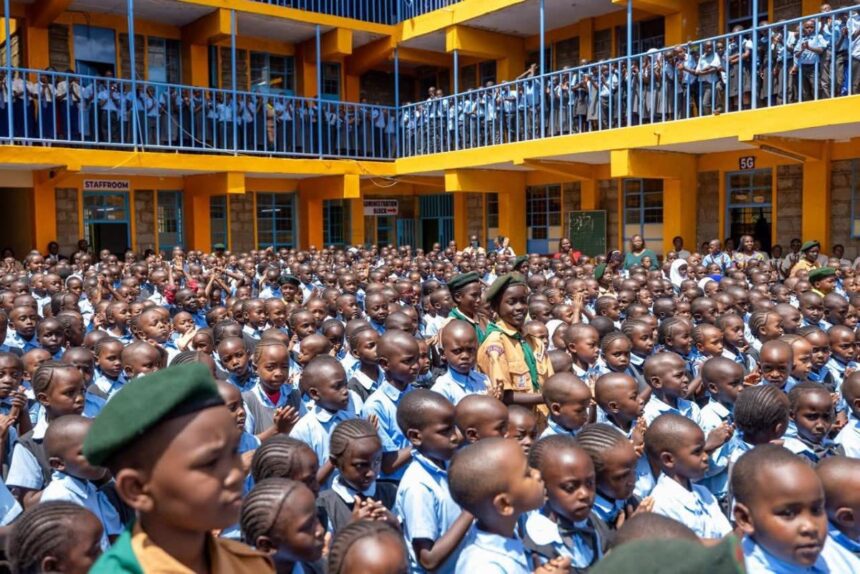

The audit warned that such shortages directly affect learning outcomes. When textbooks are unavailable, students struggle to follow lessons, revise content, or complete assignments. Over time, this leads to poor performance and widening inequality.

Wrong Books, Late Books, and No Books at All

The audit uncovered further inefficiencies that compounded the losses. In some cases, schools received textbooks for subjects they did not even offer. This resulted in wasted public funds and unusable learning materials. More than 118 secondary schools received over 134,000 textbooks for non-existent subjects. Junior and primary schools faced similar issues, though on a smaller scale. In total, over Sh30 million was spent on books that served no educational purpose.

Non-delivery also emerged as a major concern. Publishers contracted by KICD failed to deliver textbooks worth more than Sh41 million to hundreds of schools. In other cases, they delivered fewer books than required. The audit documented tens of thousands of missing textbooks across all school levels. These under deliveries breached contractual terms and undermined the goal of equitable access to education.

Delayed delivery made matters worse. Some schools received textbooks up to three years late. By then, learners had already covered large portions of the syllabus without the required materials. Such delays compromise the quality of education. They force teachers to improvise and learners to rely on shared or outdated resources. The long-term impact extends beyond exams to future opportunities.

Poor Record-Keeping and Accountability Gaps

The audit also highlighted weaknesses at the school level. Many institutions failed to maintain proper inventory records for textbooks and instructional materials. At least 110 schools were flagged for poor record keeping.

Without accurate records, it becomes difficult to track losses or confirm deliveries. Weak stocktaking practices allow errors and abuse to go unnoticed. They also make it harder to hold suppliers and officials accountable. Ironically, while some schools lacked textbooks, others received more than they needed. Excess textbooks worth over Sh90 million were delivered to hundreds of schools. In some cases, schools received more than 1,000 extra books.

Over-supply is just as wasteful as under-supply. It ties up public funds in unused materials and exposes gaps in planning and coordination. Both outcomes point to the same problem: weak systems. The audit concluded that both under supply and over supply amounted to contract breaches. Publishers failed to deliver according to agreed quantities, while oversight mechanisms failed to detect and correct the errors in time.

The findings raise broader questions about governance in public education. Efficient use of resources requires strong planning, transparency, and accountability. Without these, even well funded programmes fail to deliver value. As Kenya continues to invest heavily in education, the lesson is clear. Money alone does not guarantee results. Systems must work. Institutions must coordinate. And learners must remain at the centre of every decision. Only then can public education fulfil its promise.