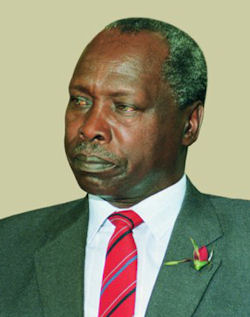

Daniel Toroitich arap Moi was Kenya’s second president and the country’s longest serving head of state, leading from 1978 to 2002. His political career spanned nearly half a century, during which he shaped Kenya’s post-independence governance, politics, and international relations. To supporters, Moi was a unifying figure who promoted peace and stability. To critics, he presided over an era marked by authoritarian rule, corruption, and human rights abuses. His legacy remains one of the most debated in Kenya’s modern history.

Early Life and Education

Moi was born on 2 September 1924 in Kuriengwo village in present day Sacho division, Baringo County. He belonged to the Tugen subgroup of the Kalenjin community. His father, Kimoi arap Chebii, died in 1928 when Moi was only four years old. He and his elder brother, William Tuitoek, were raised in a modest pastoralist environment, with Tuitoek acting as his guardian.

In 1934, missionaries selected Moi, then a herdsboy, to join the Africa Inland Mission School at Kabartonjo. It was here that he converted to Christianity and adopted the name Daniel. He later trained as a teacher at Tambach Teachers Training College between 1945 and 1947, after being denied admission to Alliance High School by colonial authorities. He also attended Kagumo Teachers College before beginning his teaching career. Moi taught at various schools and eventually became a headmaster, serving in the profession from 1946 to 1955.

Entry into Politics

Moi entered formal politics in 1955 after being elected to the Legislative Council (LegCo) for the Rift Valley seat, replacing Dr. John ole Tameno. He won re-election in 1957. As the independence movement gathered momentum, Moi served in the Kenyan delegation to the Lancaster House Conferences in London, which drafted the framework for the country’s independence constitution.

In 1960, Moi co-founded the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) with Ronald Ngala. KADU advocated federalism to protect the interests of minority ethnic communities, in contrast to the centralized governance structure preferred by Jomo Kenyatta’s KANU. However, after independence in 1963, Kenyatta persuaded KADU to dissolve and merge with KANU. Moi then joined Kenyatta’s government as Minister of Education.

Rise to Vice Presidency

Moi was elected MP for Baringo North in 1963 and later represented Baringo Central from 1966 until 2002. In 1964, Kenyatta appointed him Minister for Home Affairs before elevating him to Vice-President in 1967. As a leader from a minority community, Moi was seen as an acceptable compromise candidate in the succession politics of the 1960s and 1970s.

Despite resistance from influential Kikuyu elites known as the “Kiambu Mafia,” Moi retained his position due to support from key political figures such as Charles Njonjo and Mwai Kibaki, and from Kenyatta himself. Attempts to amend the constitution to block him from automatically succeeding the president were ultimately defeated.

Presidency (1978–2002)

Consolidation of Power

Following Kenyatta’s death on 22 August 1978, Moi became acting president and, after a largely uncontested election, was sworn in as Kenya’s second president on 14 October 1978. He began his rule with a populist, people-focused approach, touring the country and promoting national unity. However, he soon inherited and further strengthened the centralised, powerful presidency established under Kenyatta.

The 1982 Coup Attempt

On 1 August 1982, a faction of the Kenya Air Force attempted a coup led by Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka. The attempt was quickly crushed by forces loyal to Moi. The president used the event to purge perceived rivals, reduce the influence of Kenyatta-era power brokers, and entrench KANU’s authority. Shortly after, Kenya officially became a one-party state under Section 2A of the Constitution.

Authoritarian Rule and Political Repression

The 1980s were characterized by harsh crackdowns on dissent. Political opponents, activists, academics, and journalists faced detention, torture, and exile. The infamous Nyayo House torture chambers became a symbol of state repression. Marxism was banned from public universities, and opposition movements were infiltrated or crushed.

Return to Multiparty Politics

The collapse of the Soviet Union changed Western policy toward Moi. With the Cold War over, Western governments demanded democratic reforms as a condition for aid. Domestically, pressure mounted from activists in the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD) and from civil society.

In 1991, Moi conceded to international and local pressure by repealing Section 2A, restoring multiparty democracy. He went on to win the 1992 and 1997 presidential elections, both marred by violence, voter manipulation, and a deeply divided opposition.

Corruption and Human Rights Allegations

Moi’s administration faced constant criticism for corruption and abuse of power. Human rights organisations, including Amnesty International and the United Nations, documented widespread torture, political repression, and violations of civil liberties.

Moi was implicated in the Goldenberg scandal, a massive economic fraud in the early 1990s that cost Kenya over 10% of its GDP. Investigations after he left office implicated Moi and his family members in corruption and abuse of public office. Later, international arbitration bodies found that he accepted bribes in deals involving duty free airport concessions.

Reports published in 2007 revealed networks of shell companies and offshore accounts allegedly used by Moi and his associates to move large sums of public money abroad.

Retirement and Later Political Influence

Moi retired from the presidency in 2002 after endorsing Uhuru Kenyatta as his preferred successor. However, Mwai Kibaki won the election by a large margin. For one of the most dramatic political transitions in Kenya, Moi was booed at the handover ceremony, signaling widespread public resentment of his rule.

In retirement, Moi maintained a quiet but influential presence in national politics. In 2005, he opposed the proposed constitution. Around 2007, President Kibaki appointed him special peace envoy to Sudan. He later campaigned for Kibaki’s re-election and continued to speak on national issues intermittently.

Personal Life

Moi married Lena Bomett in 1950. Their marriage lasted until their separation in 1974. The couple had eight children: Jennifer, Jonathan, Raymond, John Mark, Doris, Philip, Gideon, and June. Gideon Moi later followed his father into national politics.

A devout Christian, Moi remained closely connected to the Africa Inland Church throughout his life. He founded several educational institutions, including Moi Educational Centre, Kabarak University, Kabarak High School, Sacho High School, and Sunshine Secondary School.

Illness and Death

Moi’s health deteriorated in late 2019.

He was hospitalized with pleural effusion and later underwent knee surgery. Doctors then managed several complications. He developed respiratory problems, and they performed a tracheotomy. He also suffered a gastrointestinal hemorrhage, which caused organ failure.

Daniel arap Moi died on 4 February 2020 at The Nairobi Hospital at the age of 95. His death marked the end of an era and reignited national debate over his complex legacy one defined by both stability and repression, development and corruption, unity and division.

Also read: Teacher Career Progression at Risk as TSC Requests Extra Funding